LAURA MCCULLOUGH

|

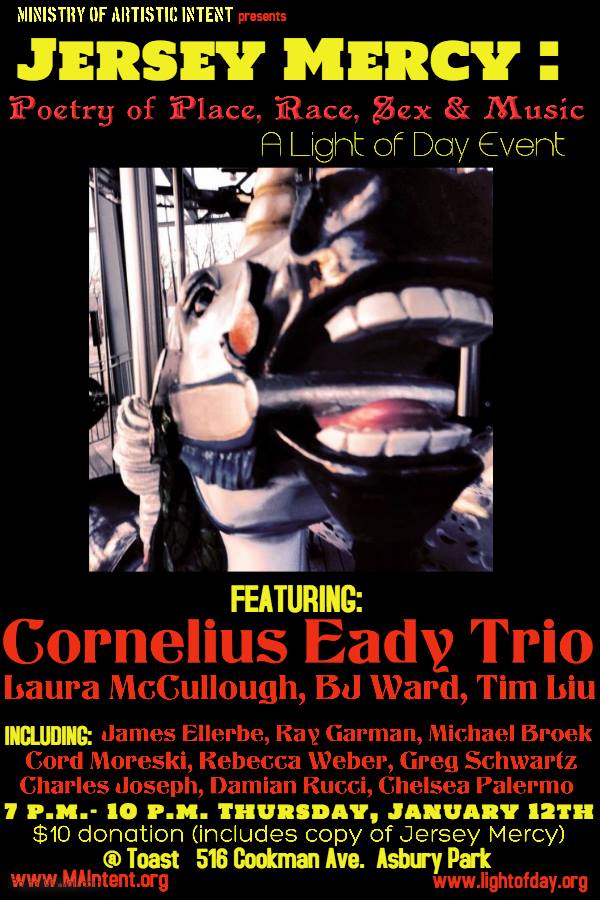

As we get ready for Jersey Mercy: Poetry of Place, Race, Sex, & Music as part of Light Of Day Foundation's Winterfest, Thursday January 12th in Asbury Park, I'm reflecting on why I wrote these poems, why I dedicated a portion the book to LoD and to people I know who have or are living with the terrible diseases the foundation raises money to combat. And I'm thinking about the idea of Jersey, the abstraction of mercy, and how they go together in my head.

I first began thinking about the difference between mercy and grace when Brent, my cousin's husband, was diagnosed with an aggresive form of ALS one February. He was dead by that September. He didn't know that previous Christmas would be his last with two young daughters, my neices, then just 2 and 6, and over the eight months from Brent's diagnosis to his passing, through the creeping paralysis that left him in the end unable to move a muscle from the chin down, he moved through suffering, we, his family, could not protect him from, but he also gained a clarity of heart in his experience. A gruff, misanthropic guy as long as I'd known him, Brent was brutally humbled, as we all were, as anyone is when faced with such a devastating disease. He was only forty when diagnosed, just forty one at his death. Just before he died, one day while I was taking a turn helping tend to his bodily care, having just cleaned the ventilator in his tracheostomy, a tube in his throat which would get gunked up with mucus, Brent began to weep. It's a terrible thing to watch someone cry when they can't move from the chin down, when they can't wipe their own tears, their own nose. He asked me to do that for him, and when he could speak again, he looked around the room, which was filled with cards and balloons and stuffed animals, all gifts of hope and care, all symbols of the many people--family, community members, local churches, volunteer groups, the kids' school--who were bringing food to his family now that he couldn't, helping clean house, take turns caring for him, helping with the kids, and more, and he said, "I didn't know how good people were." There was an astonishment in his voice and an awareness in his eyes, an utter vulnerable but epiphanic surrender to knowledge of the heart of humanity he was being confronted by through his illness and through the kindness of people he had to helplessly depend upon. In Brent's eyes, I saw something that stunned me and made me carry the tissue I'd wiped his tears with for weeks after in a pocket. I came to think what I'd seen was something like grace. I lost that tissue just like we can't hold onto grace. Mercy is described as not being punished or being saved from suffering even though we deserve what might be coming to us, while grace is experiencing a blessing or gift not because we deserved or earned it. It's hard to parse this out, but my book of poems, Jersey Mercy, is about the living music and about race and class and gender and the Jersey shore I've spent my life living along. A previous book, Panic, were also poems about the Jersey shore, about pain and loss, about the ugliness undereath the surfaces or our days and the beauty to be found even in the face of the horrendous, like Brent's experience. Panic is what I first felt; mercy is what I now try to cultivate. A few years after Brent's death, my Aunt Judy was diagnosed with Parkinson's, as was my mentor, the Pulitzer Prize winning poet, Stephen Dunn. Both of them live with this debilitating disease with gracefulness, confronting their physical challenges with humor and dignity, a dignity born of confronting human frailty. They are both funny as hell. But man, you know it's hard. Mercy in their cases might be that medical research has given them each treatments that are extending their lives, but Brent's suffering was off the charts and mercy for him might well have been the fastness of his death (eight months). But his daughters? His wife? We share suffering when someone we love suffers, and it doesn't end when they die. It lives in us. I don't know who or what doles out mercy, but I do know we can lessen suffering for each other and that this place I've lived all my life--and maybe this is true of any place we root ourselves and give ourselves to and are claimed by--is filled with people trying to be human, playing the instruments of their lives, making music alone, together, dancing in the dark, in clubs, street corners, boardwalks, in kitchens, basements, and corner shops, with each other, alone, all of us dealing with private--and collective--suffering, all striving toward something like forgiveness. My Jersey is about that. To my mind, there's nothing quite like Jersey Mercy, and Light of Day exemplifies it. And so did all the people who rallied about my cousin when he was dying, around his wife, his girls, the casseroles delivered, lawn mowings, house repairs, the volunteers who carried him in and out of the house when he had to go to the hospital, who gave Brent's wife respite when she was desperate, took her kids for icecream. And grace, too, was what I saw in them loving their dad the best they could, and his wife, man, I'll never forget this: when I and others begged her to send her husband to a facility and give up caring for him at home, she refused; again and again, she refused. She wanted to give him every dignity she could and let him stay with his family til the last moment. I remember when she called to say Brent had passed. Eight brutal months. Her voice betrayed weariness. But it was clean. So clean. She'd done it hard but right as she could manage. In my book, Jersey is a character who tries to find out who she is here on the Asbury Boards, in the backstreets of Eatontown and Long Branch, in 7-11 Parking lots and shore pizzarias. She's a stand in for all the people I've known here--myself included--facing things that want to break us, but we find a way to go on, with as much dancing as we can fit in as we do, and when someone we love falls down, we lean down with a hand to help them, haul them up if we can, or whisper something beautiful in their ear if we can't help them and have to let them go. I hope you'll come out to this inaugural poetry event and support Light of Day and its mission. We'll have some great music by the Cornelius Eady trio and poems that will talk truth to power, speak the heart's sorrows and successes, and bring a little philly, a wee bit of Newark, some NYC, and a whole lot of Jersey shore power to bear. Here are some videos from my book. Maybe you'll like them; I took all the pics and vids. Jersey Mercy Book Trailer I put together. Janna Smith, local writer and Jersey girl plays Mercy. And here's a poem video: "God Stomp Glomp" by local videogropher Dan Kaufman. This poem video was done by local artist and videographer Caleb Rechten: "The Cops Never Busted Madam Marie" It takes its title from a song by a local singer song writer you might have hear of name of Bruce. He shows up in a couple of the poems as a character. Though everyone around her has met him and has a story, I never have, so I had to write him into one. Also, when I wrote the book, I'd never gone to Madam Marie's though I'd walked by it a thousand times. I went in recently, thinking it was time. Someday maybe I'll tell someone what she told me. For now, I'll just say grace comes in a lot of forms.

1 Comment

April 15th, 20164/15/2016 Jennifer van Alstyne asks me thoughtful questions at SOMETHING ON PAPER about race in my life, how A Sense of Regard: Essays on Poetry and Race came to be, my new book Jersey Mercy, and more.

Mercy is a state of mind2/11/2016 Over the last couple of years since Hurricane Sandy, as I wrote the poems that became JERSEY MERCY, I took thousands of pics and videos of the Jersey Shore. With the help of editor Caleb Rechton, also an artist and writer, some of these have been curated along with a mashup of four of the poems in the book to make this trailer. The book is coming soon from Black Lawrence Press, my third with them. As one of the poets in Best American Poetry 2015, I have been following the Hudson Chinese pseudonym debate closely, but was hesitant to weigh in publicly for a couple of reasons, both personal. One is that this is the first time I have had a poem selected for BAP, and I was so astonished and thrilled that it makes me deeply sad to see the entire volume tarnished; the other is that as the editor of an anthology out earlier this year, A Sense of Regard: Essays on Poetry & Race, from University of Georgia Press, I might be seen as trying to jump into the talk to promote the book.

Since Walter Biggins, Senior Acquisitions Editor at UGP issued a statement about this today, I feel compelled to make clear my thinking on the matter while also supporting the poets and scholars who wrote for this project or who had their essays reprinted in it, because, indeed, as Walter Biggins points out, they do individually, as well in confluence, speak to the multiplicities that have been raised by this false identity revelation. First, I have great empathy for Sherman Alexie’s undertaking as he has explained it. As an indigenous American writer who has faced issues of white mainstream power culture, he was working toward including a diversity of many of the identity lenses that the various writers in A Sense of Regard represent. I, too, faced issues of rejecting or accepting work into the project—a project specifically trying to exfoliate issues of race and ethnicity in conjunction with other identity markers (religion, gender, class, sexuality, intergenerational wounds, politics, embodiment, etc.) in relation to poetry and poetics. The process of reviewing and considering: breaking down numbers, how many men and women (and how binary and restricted is that?) and sexualities were being represented? How many races, and what about multi-racial identifying writers? What about class? How many contributors where writing across the borders to consider poets or poetics different from their own? These were just some of the concerns in the process of putting together the anthology. Walter Biggins in his statement today mentioned a crucial essay by David Mura in it, “Asian Americans: The Front and Back of the Bus” and excerpted it. It is an amazing and humbling read, as is the one by Garrett Hongo I chose to open the anthology with, “America Singing: An Address to the Newly Arrived Peoples”. Not much, it seems, has changed, though the “peoples” are no longer newly arrived. What has changed, however, is our collective willingness, indeed, our collective sense of shared obligation to talk about these matters, and the anthology is meant to give space for thoughtful examination of race in and around poetry in such a way that it might, as I hope good poetry does, change our “sense of regard” from one position to another. Many of the essays are deeply introspective such as Tim Liu’s essay, for example, exploring his own work: why he had privileged writing about his sexuality over his Mormon heritage or being Asian American up until then. Matthew Lippman explores being a white Jewish teacher and his relationship with a young male black student while teaching Black writers. Other contributors, such as Ravi Shankar, of Pan Asian Indian heritage, wrote over borders and outside his own identify markers and examined female indigenous Indian poets. Other poets looked at ethnicity and race from their particular angles but where they intersect gendered and or political landscapes such as Lucy Beiderman writing about Jewish women writers and Philip Metres writing about poet 911 Arab American poetry. Perhaps particularly germane here are Sara Ortiz’s and Travis Hedgecoke’s essays on Native American, indigenous writers and the terrible struggles within those artistic communities. Fighting and in-fighting are in every community it seems, even the marginalized. In a word, I don’t think I am being self-serving when I champion the work of these and another 30 essayists who worked hard to make sense of the nexus of poetry and race in the anthology and that the this it is to the point in my response about Hudson’s deception and also about Alexie’s choice to keep the poem, as well as about how writers are responding, the Po-biz community, if you will, and academia. I wanted, because of my tendency to consider all sides, to be empathetic, as I tried to be in editing A Sense of Regard, to find a way to at least have some sympathy for Hudson, but I have none. It was a filthy thing to do. His explanation is banal and disingenuous at best. He’s had plenty of poems in fine journals, was in POETRY this year, not one, but two poems, and frankly it sounds as if he had sent out the poem in question just a few more times under his own name, it would likely have landed. He specifically says using a culturally and racially appropriated name was his “strategy for ‘placing’ poems” yet he was clearly doing well without lying about who he was. And this isn’t just a pseudonym for good reason (a female writing in a period when no females could be published; because of political danger; writing outside one’s genre; etc.). Hudson is clear that he was trying to prey upon who editors who are trying to be conscientious in widening the publishing net and making sure they are embracing more voices than those at the center, which have been historically white and male. I’ve thought about how he could be so cruel, so colonial, so stupid, and one thing I have arrived at is that he is not, in fact, in Po-biz, not part of academia, and those of us who do worry about the insularity of that community might take some small comfort in the idea that perhaps had this man been part of the community, he would be more involved in the discourse that has been taking place, and would, perhaps, have evolved his thinking to a point—through the many discussions and debates in the poetry world—that he would never have done such a thing. Well, I am afraid I hope for too much. But I do hope. What he did, and did multiple times, is, simply, inexcusable. No empathy, no sympathy, and my guess is the man will need a really great pseudonym after this, one he will never be able to drop if he ever hopes to “place” a poem again. As if that is the whole point of this endeavor we all share anyway. That I think, frankly, is what hurts the most: poetry to me should be the most ethical of endeavors; even if truth is mutable, we who struggle in this are all trying to refine our own aesthetic rendering of what is true through the unique lens of us, identities and all. And I understand everyone’s anger, and the anger is not specific to Asian American poets; all of us are affronted. Not least of which is Sherman Alexie. He had a decision to make when he found out. While I can only speculate about what I would have done in his place—we, after the fact, have the benefit of listening to each other as we debate this—I understand his difficult position, especially after editing A Sense of Regard, and whether I agree or not with his choice, the acrimony with which people are speaking about him and about the BAP in general is astonishing. And ugly. The very community that I wish Hudson might have learned from is also excoriating a fine writer who has championed issues of race and otherness in his life, in his work, and as an editor. In the end, it sounds as if everyone wants the “crumbs” as Ken Chen (who is a contributor to A Sense of Regard) referred to what he thought Hudson wanted. Chen said to NPR as reported in The Guardian: “American literature isn’t just an art form – it’s a segregated labour market. In New York, where almost 70% of New Yorkers are people of colour, all but 5% of writers reviewed in the New York Times are white. Hudson saw these crumbs and asked why they weren’t his. Rather than being a savvy opportunist, he’s another hysterical white man, envious of the few people of colour who’ve breached their quarantine.” The fact is that screeds against Alexie or listing name of poets not included in this year’s BAP do not address the issues that allow someone like Hudson, who seems to be a poet in isolation—a white presumably middle class male—to still have such a limited view of the world he lives and breathes in. Let’s talk about that. Let’s figure out how to change people’s sense of regard toward others. Have some empathy for the quandary Alexie found himself facing, even if you think you might have decided differently from him. And don’t throw poetry out with the bathwater. I’ve never been in BAP before, but I don’t begrudge its existence or other poets who have been in it before me. I’ve never been published in POETRY, though Hudson has. I don’t resent my friends who have been published there. There’s an awful lot of hysteria and perhaps even rhetorical opportunism going on. Which is why I didn’t blog about this until now. The truth is, there isn’t a truth here. There is complexity, and poetry, of all the arts, in my view, should be trying to hold the mysteriousness of that, trying to move in an around it using what each of us has: the singular combination of identify lenses we are all made up of. None of us, however, has a lock on the best or rightest or truthiest approach. It is an approximation, every time, as is the BAP, each year, an approximation curated by one mind, one that is considered, though not perfect. And for that, I have great empathy. For the man who could not or would not do that, who cloaked himself hoping for cultural cache and planning to trap and editor, who couldn’t write honestly as who he is and stand by it? Well, he does not have my empathy, and I said he didn’t have my sympathy, but because I can’t imagine the smallness of mind and the truncated view of the world and sorry sense of one’s place in it that he must have to do such a thing, he does have some small sympathy from me; it must be awful to live in his head, and I would wish that on no one. NOTE: I TOOK A BREAK OVER THE SUMMER POSTING EXCERPTS FROM A SENSE OF REGARD: ESSAYS ON POETRY AND RACE BUT WILL RESUME SHORTLY.  Mihaela Moscaliuc opens are brilliant scholarly essay with this: A cartoon by Matthew Diffee, published in the August 5, 2002 issue of The New Yorker shows a man answering the phone. "I'm sorry—you have the wrong language," the caption reads. You may have guessed: the man is white, casually elegant, presumably an intellectual, or at least a reader, if we are to go by the usual stereotypes: thick glasses and a thick tome he has bookmarked with his finger. Someone has interrupted his reading. Someone has assaulted his ears with foreign sounds. This someone needs to be put in his/her place: my way or the highway. This someone either owns the wrong tongue or has reached, by accident, a tongue (English) for which he/she is “wrong”—i.e., unsuitable. Either way, the non-English speaker needs to be reminded of the unassailable right of the English language to be the “right” language. The man’s genteel, if perfunctory, “I’m sorry” and his mismatching facial expression (perhaps offended, perhaps repulsed) capture the tenor of some of the prevalent concerns about the future of the American national language. Today, the anxiety stamped on the man’s face would be exacerbated by on-going debates on bilingualism/multilingualism and on the potential of immigration reforms to forestall, decelerate, or accelerate transformations within dominant national discourses. And closes it thus: We know that American English has always been, and continues to be, a language-in-the-making, regardless of our chronic fears of contamination, but we do not know, of course, the extent to which the non-English languages of the nation will (be able/allowed to) participate in such processes of transformation. We do know, however, that the recombinant dictions of Nuyorican, “borderlands,” and Chicano poets (as those mentioned here, as well as others, such as Victor Hernández Cruz, Giannina Braschi, and Guillermo Gómez-Peña) have the poetention of exacting change. Moreover, these poets are not alone, of course, in recalcitrating against the ethnocentrism of English. Others, such as Kimiko Hahn (in “The Izu Dancer”), Barbara Jane Reyes (in Poeta in San Francisco), and R. Zamora Linmark (in The Evolution of a Sigh and in other works), make visible in their poems the dialogues and clashes between languages and cultures and unsettle, in the process, various hierarchies of values upheld by the dominant culture. Their use of Spanish, Japanese, Chinese, Tagalog, Filipino English (Taglish), or Hawaii creole, and direct engagements with issues of translatability interrupt and disturb — productively, I would argue - normative readings practices. Perhaps in time these poets will alter reading expectations as well, making us less likely to respond with “Sorry—you have the wrong language.”  Patrick S. Lawrence's essay looks deeply into one African American poetic landscape of contigency, alienation, and American re-animation: Little critical work has been done on Nathaniel Mackey’s Splay Anthem (2006), a collection of installments of his two serial poems Song of the Andoumboulou and “Mu”. However, because other sections of the two poems have appeared over the past several years in venues such as Callaloo, African American Review, Chicago Review, and The Nation, there is a body of critical writing on the ongoing concerns of the portions of the poems appearing outside the collection that can shed light on how they are worked out in Splay Anthem, which won Mackey the 2006 National Book Award for poetry. As Mackey has continued to explore certain themes throughout the life of the poems, we gain added value from returning to this prize-winning collection and re-assessing the poems’ significance in a changing world. Though Song and “Mu” were begun in the later part of the twentieth century, they take on new meaning in the context of the events that have occurred contemporaneously with their continued publication. Thus, a more complete focus on the poems and their Modernist/Postmodernist techniques can shed light on the developing relationship between experimentation and politics, a relationship that has been fraught since the 1960s at least. Splay Anthem’s indirect political project acknowledges that the work of striving for equality and community is ever-incomplete, but provides a tentative foundation for this effort. Splay Anthem is a weave of several themes and recurrent experimental forms. Jarring enjambment causes lines to read both with those that came before and those that follow with ambiguity, while often refusing to signify concretely. This is in keeping with the effect of the variations-on-a-theme style of polysemy used throughout the poems, in which words are exploited for their double (or multiple) meanings, often with plural meanings suspended simultaneously, refusing to resolve in clear reference. Mackey’s use of the word rung, for example, signifies simultaneously both the past tense of to ring and the lateral cross-pieces of a ladder. Additionally, words often appear in alienated forms, used repeatedly with slight changes to spelling but retaining just an echo of their other forms. The themes that emerge amid this weave are complex and epic, following an incomplete but continuously striving humanity as it searches for a communal, global identity. This process is difficult and often painful. It is evinced by Mackey in his preface, where he explains what he means when he uses the word Andoumboulou: The song of the Andoumboulou is one of striving, strain, abrasion, an all but asthmatic song of aspiration. Lost ground, lost twinness, lost union and other losses variably inflect that aspiration, a wish, among others, to be we, … that of some larger collectivity an anthem would celebrate. (2006, xi) To read the entire essay and the rest of the collection get A Sense of Regard: essays on poetry and race  Excerpt of his essay: The accepted contemporary subtexts of American literary whiteness include the whole long shadow of American racial injustice, first, of slavery, and secondly, of ongoing economic and social inequality—haunting realities. We stand indefinitely, and anxiously, in their shadows. Another part of the shadow is ongoing white privilege, and the natural instinct to retain advantage. Take myself as an example. On the one hand, I'll acknowledge my privilege readily; on the other hand, I hope not to be inconvenienced. Secretly too, my ego will privately continue to believe that whatever success I have experienced has been legitimate, is appropriate, and has been earned by my individual talent and hard work. These are called subtexts for a reason; I will never say this openly, because of the hazard that accompanies frank expression in the public forum on the topic of race. The topic itself, everyone knows, has become the territorial property of persons of color. Thus, the frank, exploratory, spontaneous speech that our shared reality requires can easily end in blame or disgrace. Thus I won't ever disagree, openly, with the consensual liberal parameters of the racial conversation. I will be a yes-person. Occasionally, in a marginal way, among my liberal white friends, I will ironically acknowledge that the machinery of affirmative action is at work in the cultureplace. This calculation of equity (counting heads) is the price of repairing history. I consent to the machinery, and, though I would personally prefer not to pay the disadvantageous price of it—oh well, it's not about me. My main public obligation is to appear unconflicted. Whether I feel good about it or not, to be conflicted about race would, in itself, be an admission of confusion about these labyrinthine American matters. Confusion is suspect. The gap between these two unconscious positions—the position of historical plaintiff, played that evening by Alexander, and the position of uneasy, but secure self-righteous possessors of privilege, played by myself—is substantial, and, so far, mostly unbridged. Both positions seem a little petrified or fossilized. Our consensual silence—the particular silence of white liberals—on the subject of race is, paradoxically, ultimately an obstacle to acknowledging the present and moving into the future. It's not hard to see that we—both white and black poets—are still breathing through straws. Brothers and sisters—am I allowed to say that?—we are haunted. One question is: can a conscious poetry help bridge it? To read Tony's essay and his answer to that question, and to read all the others, you can get the anthology here. Making Enemies: Ailish Hopper4/14/2015  Ailish Hopper’s “The Gentle Art of Making Enemies” considers the destabilizing, re-assembling and re-visioning of race through poetry, and the gestures, strategies, and maneuvers of many poets currently working in this vein. Read a couple of excerpts of her well researched essay: Challenge the codes [regarding race] and you will be punished by their enforcers---who may be black or white. This protective border serves what James C. Scott calls the “public transcript,” which justifies and prosecutes its “rules” that are by nature hidden. They can only be expressed in codes, euphemisms, and other forms of disguise, which appear as simply agreed-upon, unanimous. Meanwhile there exists a “hidden transcript,” the things that are said away from the gaze of the racial codes and their enforcers. (1990, 45) As in the rest of the world’s activities, poetry, publishing, and criticism numbingly and brutally reflect this dynamic, what Marcel Cornis-Pope calls, “narratives of containment” (2001, xii). ... [A]nger, is equally distorted across the racial spectrum. For white poets, for instance, pain is only visible in its neurotic forms, e.g., “white guilt,” which is merely another version of white refusal. Real accountability, naming the stage and the script we all stand on and speak from, is thus an important rupture. Martha Collins acknowledges that: “…a few years after Brown/ v. Board of Education [she] wrote a paper/ that took the position Yes But not yet,” not adding a narrative of remedy, despair, or even hope (2011, 1). She simply opens this closed space in history and lets stand her naked complicity. This poetics is thus a cold shower not only on history, but on our readerly desire to be soothed or to find sympathetic understanding. Rewriting aims to disrupt what Brecht called a “hypnosis” between that can happen between poem and reader, if it is based on stable, but false, notions of our own, and others’, identities. (1961, 12) Inside this hypnosis, all manner of racial codes can safely be transmitted, with the reader unaware. This disruption, since language is so complicit, too, is well assisted by visual language or actual images. Claudia Rankine, in Don’t Let Me be Lonely, pairs a poem with an illustration by John Lucas that makes material the social internalization of “toxic” racialization: TO READ THE FULL ESSAY AND ALL OF THE OTHER, YOU CAN GET THE ANTHOLOGY HERE Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed